Building Pipelines with Circular Buffers, not Queues

Structuring programs as pipelines is a nice way to separate business logic and introduce parallelism - if you do it right it gets you both clarity and performance.

Typically this is done by tying threads together with some form of concurrent queue, such as a channel in Golang, ConcurrentLinkedQueue in Java, or concurrent_queue in C++ (Intel TBB or Microsoft PPL).

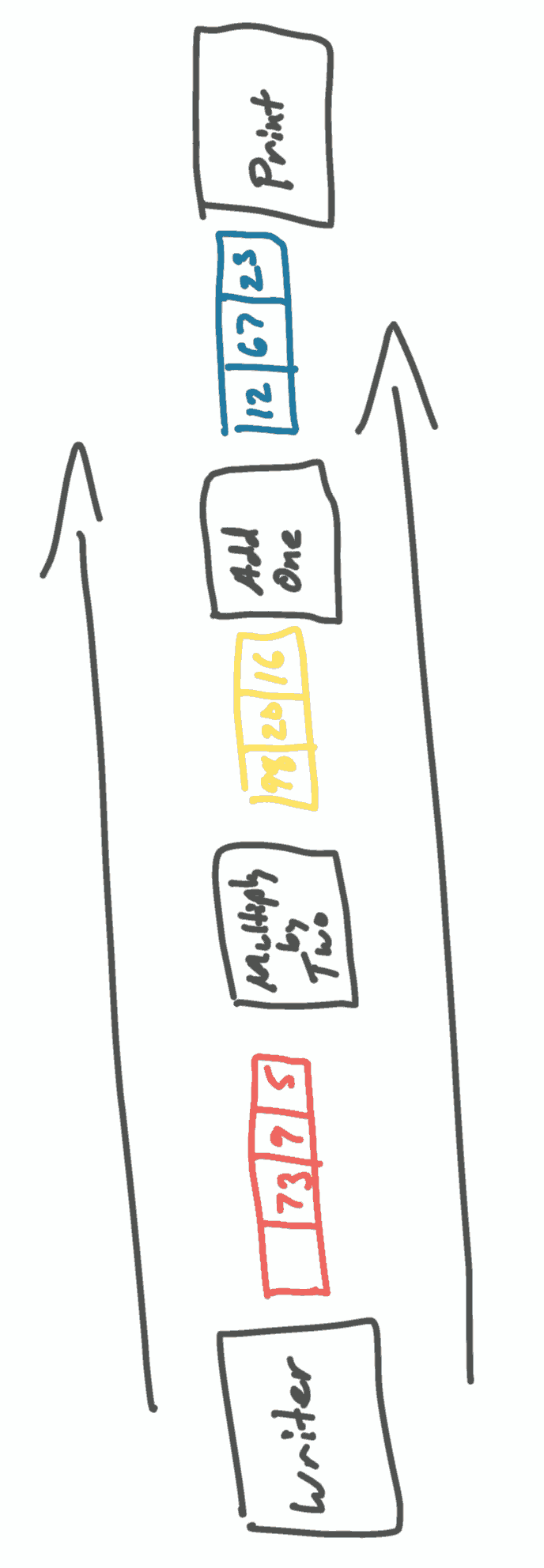

Using a simple integer pipeline as an example, we’ll have an initial phase writing random integers, one phase that multiplies its input by two, one phase that increments its input, and a final phase that prints the result.

With queues, it would look something like this:

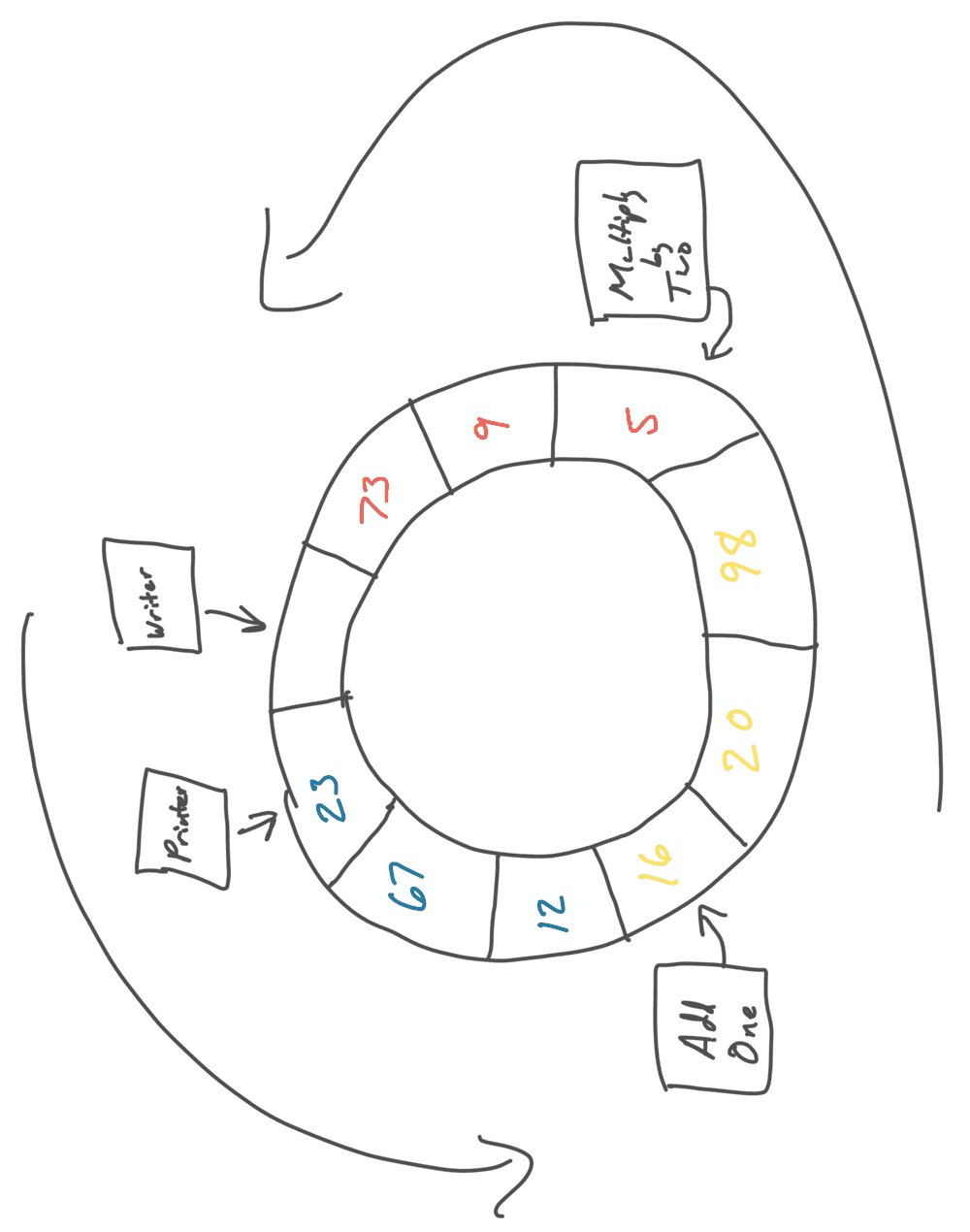

But the overhead of multiple queues can be quite high and variable, so is often unacceptable in low-latency programs. An alternative is to use a single circular buffer and have each thread hold a cursor into it. This pattern has significantly better behavior on current hardware and requires minimal synchronization. It’s variously known as event sourcing, the LMAX Disruptor, or “that giant circular buffer pattern.”

A shared circular buffer for our example would instead look like this:

One way to think about this is that we’re moving the executor to the data instead of the data to the executor.

A few of the advantages:

- Extremely good data locality. The prefetcher will pull data for the next item into the cache before we need it and we’ll keep the CPU well-fed and happy.

- No data needs to be copied between phases, whereas the queue needs a copy in/out of the queue. As the struct gets large the queue needs to start using a pointer indirect, which again hurts locality and puts more pressure on the gc. Since we don’t incur any expensive copies, the buffer can continue to store large structs directly. If our struct is written appropriately we also won’t need to do any expensive clean operation on struct reuse.

- Low contention. Each phase coordinates with a single atomic and one sync operation can batch multiple items at once (ie. we only do one sync to take ownership of all queued items for our phase), compared to a queue which typically must synchronize on each item.

- Very few pointers for the gc to scan, possibly just the pointer to the circular buffer and pointers between phases. With care we could code it to generate zero garbage when in steady state.

- Performance is consistent. Where the queue has multiple buffers that need to be sized, locks that may be contended, etc. it’s much easier in the circular buffer to quantify the total amount of work in the system and the worst-case performance under full load.

A very barebones example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"runtime"

"sync/atomic"

)

type data struct {

num int

}

type phase struct {

_ [7]int64 // padding

cursor int64

_ [7]int64 // padding

upstream *phase

}

const bufSize = 64 // must be power of 2

const bufMask int64 = bufSize - 1

var circularBuf [bufSize]data

func runPhase(p *phase, f func(int64)) {

curr := int64(0)

for {

upstreamLimit := atomic.LoadInt64(&p.upstream.cursor)

for curr != upstreamLimit {

f(curr&bufMask)

curr++

}

atomic.StoreInt64(&p.cursor, curr)

runtime.Gosched()

}

}

func runWriter(p *phase) {

r := rand.New(rand.NewSource(1))

curr := int64(0)

for {

upstreamLimit := atomic.LoadInt64(&p.upstream.cursor)

if curr == upstreamLimit {

// empty buffer

upstreamLimit = curr + bufSize - 1

}

for curr&bufMask != upstreamLimit&bufMask {

circularBuf[curr&bufMask].num = r.Intn(100)

curr++

}

atomic.StoreInt64(&p.cursor, curr)

runtime.Gosched()

}

}

func main() {

// writeRandInt -> multTwo -> addOne -> printResult

var printResult, addOne, multTwo, writeRandInt phase

writeRandInt.upstream = &printResult

printResult.upstream = &addOne

addOne.upstream = &multTwo

multTwo.upstream = &writeRandInt

go runWriter(&writeRandInt)

go runPhase(&addOne, func(i int64) {

circularBuf[i].num++

})

go runPhase(&multTwo, func(i int64) {

circularBuf[i].num *= 2

})

go runPhase(&printResult, func(i int64) {

fmt.Println(circularBuf[i])

})

select {} // block forever

}

This code is meant to show off the core concept in the smallest amount of code possible. Fully building this out you would hide the cursor logic behind a nice API and the final business logic would look very similar to a queue-based implementation looping on a consume function.

A few specific notes about the implementation:

- The cursors are not truncated to the size of the buffer each time they’re incremented, instead they count towards integer max and wrap. This makes it easy to disambiguate completely empty buffers from completely full buffers.

- The example has no backoff or wait strategy. Busy spin is what you’d want for a high-load, low-latency system, but something that trades a small amount of performance to let the CPU idle is preferable in other cases. Ideally this would be implemented with direct calls to gopark/goready, but those aren’t exposed externally by the runtime. A condvar can be used instead.

- The example also has no batching strategy except “grab everything available”. This will lead to clumping, but fixing is trivial.

- On x86_64, atomic loads are compiled to

movand atomic stores are compiled toxchg. arm64 compiles these toldarandstlrrespectively. This is standard, but was my first time looking at the asm for atomics in golang, so I was happy to see solid codegen. - The conditional for the empty queue case in the writer is unfortunate. Ideally we would write that conditional as straightline code, eg.

upstream = atomic.LoadInt64(&p.upstream.cursor)

empty = curr^upstream == 0

upstreamLimit = (upstream * !empty) + ((curr + bufSize - 1) * empty)

This would generate a cmp but no jmp. Unfortunately I know of no way to

express this in go, and the optimizer doesn’t do it for us. It is a common pattern

in C and other systems programming languages.

Since we know the numbers are positive but we’re saving them in 2s complement,

in this case we do have a path to doing this with computation, but it’s

silly and mostly academic.

upstream := atomic.LoadInt64(&p.upstream.cursor)

notEmpty := curr ^ upstream

upmult := (notEmpty >> 63) - (-notEmpty >> 63)

upstreamLimit := (upstream * upmult) + ((curr + bufSize - 1) * (^upmult & 1))

Update: turns out there is a way to express this. At least as of go 1.19, this

generates the assembly I’m looking for - straightline code with a cmp but not jmp.

upstream := atomic.LoadInt64(&p.upstream.cursor)

empty := int64(0)

if curr^upstream == 0 {

empty = 1

}

upstreamLimit := (upstream * (empty^1)) + ((curr + bufSize - 1) * empty)

One last note: channels in go are deeply integrated with the runtime and do things like make explicit gopark/goready calls, copy values from one goroutine’s stack directly into another’s, etc. You could do a lot worse, and should make sure they don’t fit your needs before rolling your own.