Fast Subnet Matching

Determining if a subnet contains a given IP is a fundamental operation in networking. Router dataplanes spend all of their time looking up prefix matches to make forwarding decisions, but even higher layers of application code need to perform this operation - for example, looking up a client IP address in a geographical database or checking a client IP against an abuse blocklist.

Routers have extremely optimized implementations, but since these other uses may be one-off codepaths in a higher-level language (eg. some random Go microservice), they’re not written with the same level of care and optimization. Sometimes they’re written with no care or optimization at all and quickly become bottlenecks.

Here’s a list of basic techniques and tradeoffs to reference next time you need to implement this form of lookup; I hope it’s useful in determining a good implementation for the level of optimization you need.

Multiple Subnets

If you have multiple subnets and want to determine which of them match a given IP (eg. longest prefix match), you should be reaching for something in the trie family. I won’t cover the fundamentals here, but do recommend The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 3 for an overview.

Be extremely skeptical of any off-the-shelf radix libraries:

- Many do not do prefix compression

- Many support N instead of two edges, which may lead to unnecessary memory overhead

- Many will operate on some form of string type to be as generic as possible, again contributing to memory overhead

- All be difficult to adapt to different stride lengths

I would highly recommend writing your own implementation if performance is a concern at all. Most common implementations are either too generic or are optimized for exact instead of prefix match.

unibit to multibit to compressed

A radix 2 trie that does bit-by-bit comparison with compression for empty nodes is a good starting point. To further speed it up, you’ll want to compare more than one bit at a time - this is typically referred to as a multibit stride.

Multibit strides will get you significantly faster lookup time at the cost of some memory - in order to align all comparisons on the stride size, you’ll need to expand some prefixes.

As an example, let’s say you’re building a trie that contains three prefixes:

- Prefix 1: 01*

- Prefix 2: 110*

- Prefix 3: 10*

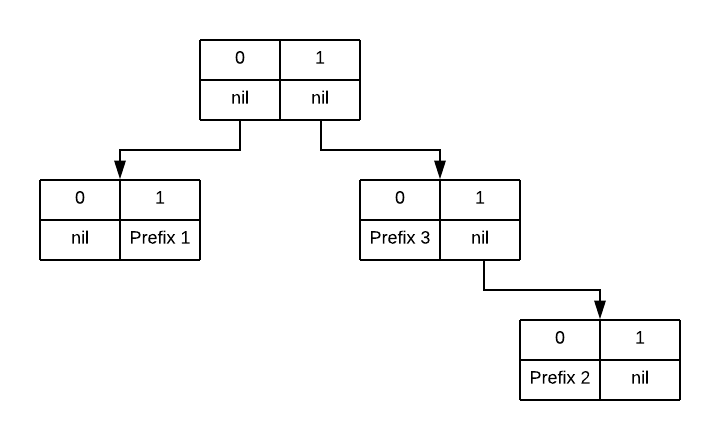

A unibit trie would look like this:

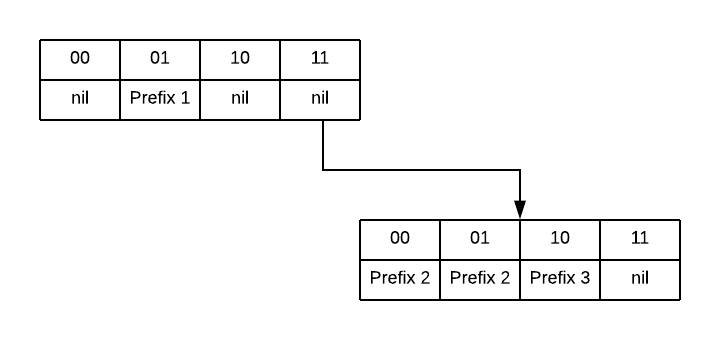

If instead we want to use a multibit trie with a stride of two bits, then prefix 2 needs to be expanded into its two sub-prefixes, 1101* and 1100*. Our multibit trie would look like this:

Note how this trie has incresed our memory usage by duplicating prefix 2, but has reduced our memory accesses and improved locality (there are far fewer pointers chased in this diagram), thus trading memory usage for lookup performance.

Most of the time a multibit trie is where you can stop. If you need to optimize further, especially if you need to start reducing memory usage, then you’ll want to explore the literature on compressed tries. The general idea with many of these is to use a longer or adaptive stride, but find clever ways to remove some of the redundancy it introduces. Starting points include LC-tries, Luleå tries, and tree bitmaps.

Modified traversals

There are some common, related problems that can be solved by small modifications to the traversal algorithm:

- If instead of finding the longest prefix match you need to find all containing subnets, simply keep track of the list of all matching nodes instead of the single most recent node as you traverse and return the full set at the end.

- If you need to match a containing subnet on some criteria other than most specific match, for example declaration order from a config file, express this as a numerical priority and persist it alongside the node. As you traverse, keep track of the most recently visited node and only replace it if the currently visited is a higher priority.

Sidenote on PATRICIA tries

PATRICIA tries are a radix 2 trie that saves a count of bits skipped instead of the full substring when doing compression. You don’t want this! They’re great for exact match lookup, like what you’d want in a trie of filenames, but saving only the skip count causes prefix matches to backtrack, resulting in significantly worse performance. It’s unfortunate that they’re so often associated with networking; in some cases the name is misused and people say PATRICIA when they simple mean radix 2.

Single Subnet

If you have a large number of IPs and want to check if a single subnet contains them, spend a little time looking at your assembler output to choose a good implementation. If available, you’re best off using 128-bit literals to support IPv6. C, C++, Rust, and many systems languages will support this. Unfortunately Go and Java do not, so you’ll have to piece it together with two 64-bit integers - slightly cumbersome, and slightly more overhead as we’ll see.

In IPv4, subnet contains checking is easy since everything fits in a word, roughly:

// checking if 1.2.3.0/8 contains 1.2.3.4

uint32_t prefix = 0x01020300; // prefix address, packed big endian

uint32_t client = 0x01020304; // client address, packed big endian

uint8_t mask = 8; // netmask, range 0-32

uint32_t bitmask = 0xFFFFFFFF << (32 - mask); // invert the mask to get a count of number of zeros

if ( (prefix & bitmask) == (client & bitmask) ) {

// subnet contains client

}

IPv6 is when things get interesting. 128-bit long IPv6 addresses means juggling two machine words. In computing the bitmask we need a mask for the upper and the lower portion of the address.

uint64_t upper_prefix, lower_prefix, upper_client, lower_client = ; // assume these are initialized

uint8_t mask = ;// netmask, range 0-128

uint64_t upper_bitmask = UINT64_MAX;

uint64_t lower_bitmask = UINT64_MAX;

if (mask < 64) {

lower_bitmask <<= mask;

} else {

upper_bitmask = lower_bitmask << (64 - mask);

lower = 0;

}

if ((upper_prefix & upper_bitmask) == (upper_client & upper_bitmask)

&& (lower_prefix & lower_bitmask) == (lower_client && lower_bitmask)) {

// subnet contains client

}

Rewriting with gcc/clang’s int128 emulated type:

__uint128 prefix, client = ; // assume these are initialized

uint8_t mask = ;// netmask, range 0-128

__uint128 bitmask = std::numeric_limits<__uint128_t>::max() <<= (128 - mask);

if ( (prefix & bitmask) == (client & bitmask) ) {

// subnet contains client

}

The emulated int128s are much easier to read and work with, but how does performance compare?

Here is the source code and Godbolt link for a small test, isolating just the shift portion:

#include <cstdint>

__int128 shift128(uint8_t shift) {

__int128 t = -1;

t <<= shift;

return t;

}

struct Pair {

uint64_t first, second;

};

Pair shift64(uint8_t shift) {

uint64_t upper = -1;

uint64_t lower = -1;

if (shift < 64) {

lower <<= shift;

} else {

upper = lower << (shift - 64);

lower = 0;

}

return Pair{upper, lower};

}

And here is the compiler’s optimized x86 assembly with comments added:

shift128(unsigned char):

mov ecx, edi ; load mask into ecx

mov rax, -1 ; initialize lower word

xor esi, esi ; zero this register for use in cmov

mov rdx, -1 ; initialize upper word

sal rax, cl ; shift lower word by mask

and ecx, 64 ; and our mask with 64

cmovne rdx, rax ; move lower word into upper

cmovne rax, rsi ; zero lower word

ret

shift64(unsigned char):

movzx ecx, dil ; load mask into ecx

cmp dil, 63

ja .L4 ; jump if mask is >= 64

mov rdx, -1 ; initialize lower word

mov rax, -1 ; initialize upper word

sal rdx, cl ; shift lower word by mask

ret

.L4:

sub ecx, 64 ; find out how much we need to shift the upper word by

mov rax, -1 ; initialize upper word

xor edx, edx ; mask was >64, so just zero the lower word

sal rax, cl ; shift upper word

ret

There are a few interesting things to note:

salwill automatically mask its shift operand to the appropriate range, so while it’s undefined behavior in C to shift by more than the size of the target, this is fine at the asm levelandwith 64 is using knowledge of undefined behavior - our shift is only well-defined within the range of 1-127, so we assume UB is impossible and ignore the range outside.cmovis used instead of a jump. On modern hardware this should be strictly better, though is most noticeable when jumps are unpredictable. Our jumps should be very predictable here.

If we wanted, we could rewrite the int64 version in a way that would more closely match the int128 assembly:

Pair shift64_v2(uint8_t shift) {

uint64_t upper = -1;

uint64_t lower = -1;

lower <<= (shift & 0x3F);

if (shift > 0x3F) {

upper = lower;

lower = 0;

}

return Pair{upper, lower};

}

shift64_v2(unsigned char):

mov ecx, edi

mov rdx, -1

mov rax, -1

sal rdx, cl

cmp dil, 63

jbe .L4

mov rax, rdx

xor edx, edx

.L4:

ret

Note how the assembly does not contain any explicit and with 0x3F, we’ve

merely communicated to the compiler that we want the sal instruction’s

default mask behvior. Our cmov has also been converted to jmp.

Previously I’d hoped that I could use the 128-bit SSE registers and mm

intrinsics to operate on IPv6 addresses natively. However, operations to use

SSE registers as a single 128-bit value (as opposed to 2 64-bit values, 4

32-bit values, etc.) are quite limited. In particular, _mm_slli_si128 shifts

by bytes instead of bits so won’t work for our use case (though SIMD

instructions would be useful for performing matches against multiple client IPs

at once).